The French city of Arles is filled with contrasts—you could even say ironies.

The French city of Arles is filled with contrasts—you could even say ironies.

It begins with geography: an ancient city in the South of France built by the Romans on a marshland beside the Rhone, Arles is swimming in humidity and still heat one day. The next, it is swept by a fierce, dry wind—the Mistral—as sharp and piercing as you might expect before a sandstorm.

In fact, our early impression of the city as a paradise of mosquitos the first night of our visit was soon belied by this blast of Siberian air that blasted the annoying insects straight out of sight. I’d originally thought the Mistral was a sort of Southern French legend without much basis in fact, much like the Yeti or Loch Ness monster. I was quite wrong—the people of Provence were not exaggerating its strength.

But just as striking to the visitor is the legacy of another visitor who came to Arles, Vincent Van Gogh, who seems to hover over the city like a ghost, by turns benevolent and wrathful—and, most of all, lucrative.

The Dutch Van Gogh, who’d previously lived in London and Paris, came to Arles in 1888 for the light, he wrote to his brother Theo, an art dealer who gave him much encouragement. Van Gogh loved how bright everything was there compared to the rain-soaked north. The landscape also reminded him of Japan, he said, a great inspiration. He hoped to found an art colony in Arles and make the city a real destination for artists and art-lovers.

Van Gogh’s painting was incredibly prolific and innovative during his one year and three months in Arles. Many famous works were done in the city and in the nearby town of St Remy-de-Provence, a few miles away (where he went directly after Arles, voluntarily confined to the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum there). He produced around 300 drawings and paintings during the short period he lived in Provence.

Imagine the painter at night, the sweep of the Rhone River below him, sticking candles in his straw hat to provide light in the dark, and then painting a starry night scene over the water.

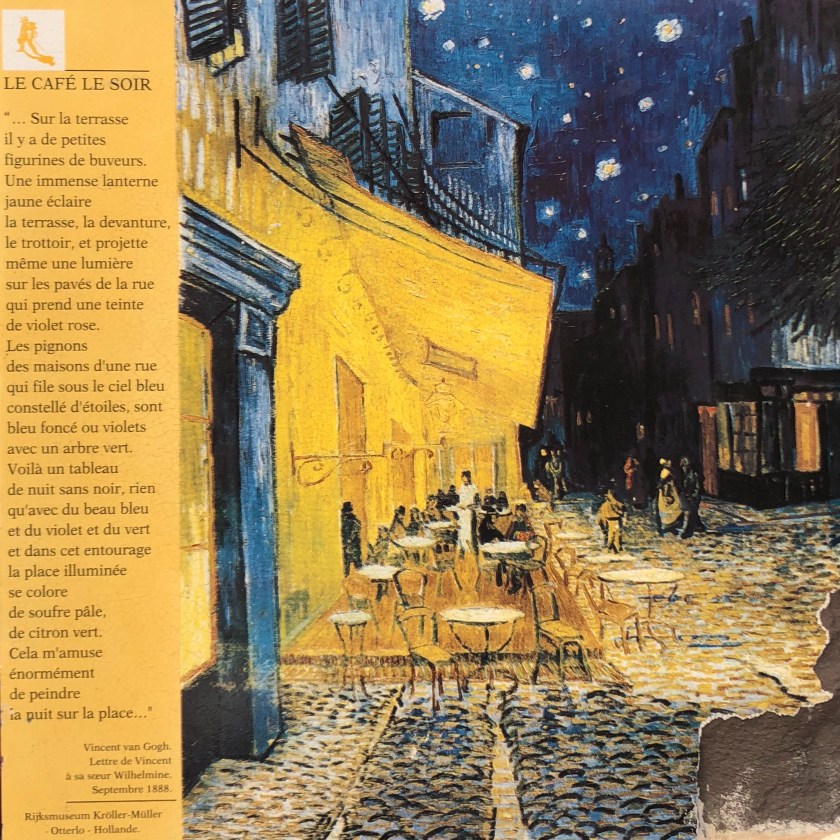

Imagine him depicting a bright yellow café lit up in the evening in the Place du Forum, its wide awning beckoning passersby to come and have a drink.

Imagine the people of Arles, irate, so angry that they started circulating a petition to force Van Gogh to move out of town.

That’s the part of the Van Gogh story that you may not hear so much about if you travel to Arles. Van Gogh, a “redhaired madman” (“fou roux”), as some called him, became known for acting erratically. He had been hearing voices, and he frequented brothels and drank heavily. Some (including his painter friend Paul Gauguin) found him physically threatening. Then—in an incident that has been used to sum of Van Gogh’s madness ever since—he severed his own ear and gave it to a prostitute he knew.

Van Gogh was taken to the hospital in Arles for a period—where he continued to paint, including an image of the flower-filled hospital courtyard—and began to recover, returning to his home. But the hallucinations continued.

At that point, 30 Arlesians who signed a petition to force out Van Gogh made their wishes known. The authorities made Van Gogh leave the Arles “Yellow House” where he lived, and soon after he made his way to the asylum in St. Remy.

He continued to produce bright, beautiful paintings. Nevertheless, his troubles continued, and he committed suicide near Paris not long after.

Today it’s quite a different reception for Van Gogh in Arles’ tourist materials, local sites, art museums, and shops. Everywhere it’s Van Gogh. There’s the Espace Van Gogh, an art institution that was formerly the hospital, and the Fondation Vincent Van Gogh, housed in a 15th-century mansion, which features a handful of his paintings and many works “inspired” by him as well as other contemporary exhibits.

There are numerous outdoor reproductions of his paintings forming “easels” scattered around town, in spots where Van Gogh created his art. My family used those to organize a walking tour through the city.

Some have tried to capitalize by recreating what Van Gogh saw. The “Night Café” he painted in bright yellow is there today on the Place du Forum, again brilliant yellow thanks to its current owners. Our guidebook warned it is a tourist trap, so we just walked by and ate at another restaurant. Many foreign tourists we observed seemed to focus almost exclusively on Van Gogh sites in Arles.

What was once hatred has blossomed into love, appreciation, and international commerce.

It’s a very friendly commerce. Shopkeepers and small stall-keepers in Arles were among the nicest and most patient that I’ve encountered anywhere in France. They explained, guided, and even made a little conversation with yet another tourist in their midst. I didn’t begrudge them at all wanting to give the public a piece of Van Gogh’s artistic legacy to take home, and to make a few Euros in the process.

I happily participated in the capitalist celebration of this tragic genius, coming home with a Van Gogh tote bag, Van Gogh calendar, Van Gogh pocket flashlight, and pillbox, not to mention a magnet and numerous postcards. (In my defense, several of these were gifts.)

And now, when I see artwork by the master, I’ll think of the windswept streets, the quiet gardens, and the expansive riverbanks of Arles.

Next time: Van Gogh’s dream of making Arles an arts destination is becoming a reality today. Find out how.